Bullet Hell Game - Snowy Standoffs (Page Under Construction)

Video link:

Languages: DNH (C-Like Scripting Language)

About

One of the many projects I have made within the engine Danmakufu. These projects focus more on gameplay and design, as well as

my dedication to complete large tasks and manage solo projects.

As this is one of my largest projects, feel free to just skim through the demonstration video if you are pressed for time. There is a lot for me to discuss and I would be happy to go into

further detail on the aspects I do not bring up on this page.

Note: The video link provided is temporary and is a part of a demonstration stream.

Key Skills Used

- Time Management

- Project Management

- DevOps

- Agile

- Visual Debugging

- Version Control

- GitHub

- Teamwork and communication with asset creators and playtesters

- Creativity

- HLSL Code

- Game Design

- Risk Assessment

- Brainstorming and Concept Art

- Menu and UI Design

- Game Feel

Brief Engine Background Knowledge

Due to how niche this engine is, a brief explaination of the engine is probably needed. In short, Danmakufu is a 2D engine designed specifically for the creation of bullet hells. It’s optimised to handle a large amount of projectiles on screen and was initially created for japanese fans of the ‘Touhou’ series to make their own inspired games. Everything is coded in the scripting language ‘DNH’, which resembles C. By default, the engine comes with the basics of a game engine (sprite rendering, sound ect.) but in comparison to more well known engines, it’s increadibly lacking. Despite all this, it is still the main choice of engine when it comes to making Touhou-inspired games due to many of the most popular fangames using this engine.

Context

DISCLAIMER: This game is part of the annual Shrines and Youkai Secret Santa. This is a derivative work of fiction, containing concepts from other existing media. All characters that appear in this work are a part of the S&Y universe.

This is a project I am currently working on a project which I started in October and initially finished on Christmas day. This was initially a gift made for someone as part of a Secret Santa event, but with my recipient’s permission I am able to eventually release this publicly. This project can be seen as a culmination of everything that I have learned over the 10 years of learning this niche engine. Because of the

small audience this was initially intended for, there are a lot of elements this game expects you to be familiar with beforehand such as controls, strategy and story context.

Though I do not intend for this to be my final work within this medium, this is by far the grandest game I have made so far. For this project, I worked on the code, the artwork, the design, the enemy attacks, the backgrounds and

much more. This was primarily a solo project, however I had some help with writing towards the end of the project. Full details are given during the credits sequence.

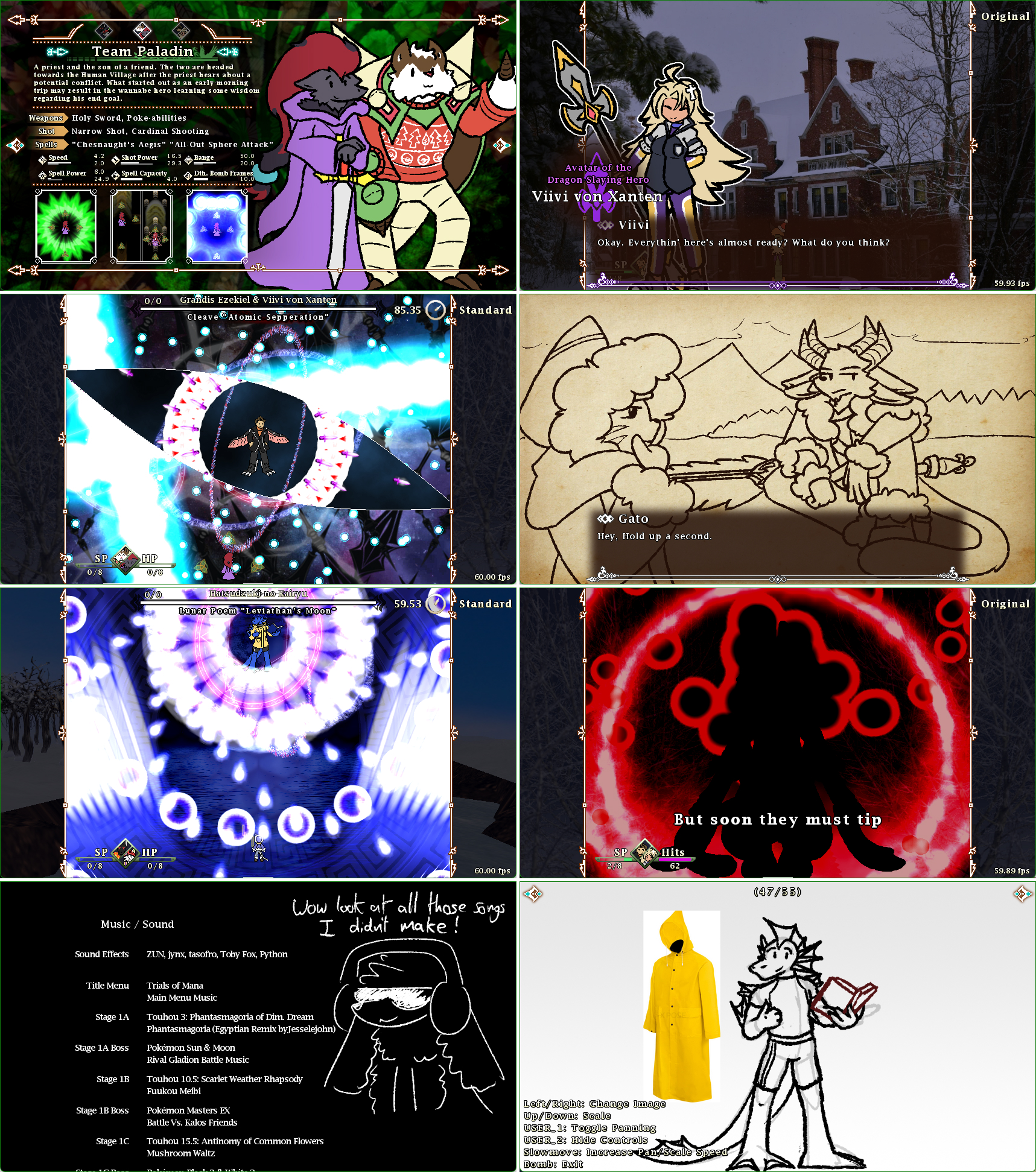

In total, the project as of December 2024 contains:

- 3 playable routes with unique dialogue and ending sequences

- 6 stages, with 3 varients for stage 1 and 4

- 63 total boss patterns

- Over 1100 lines of dialogue

- 15 characters with complete dialogue portait components

- A loading sequence, main menu, game progression, ending and credits sequence

- A funcitonal options and practice menu

- Save data and unlockables

A lot of the hard work is pretty much done, just missing the regular stage portions for each stage. Once the stage portions are complete, there will be a full release. But for now, I can provide a link to those who view my portfolio.

GitHub link at: https://github.com/JunkyX1122/secret-santa-2024.

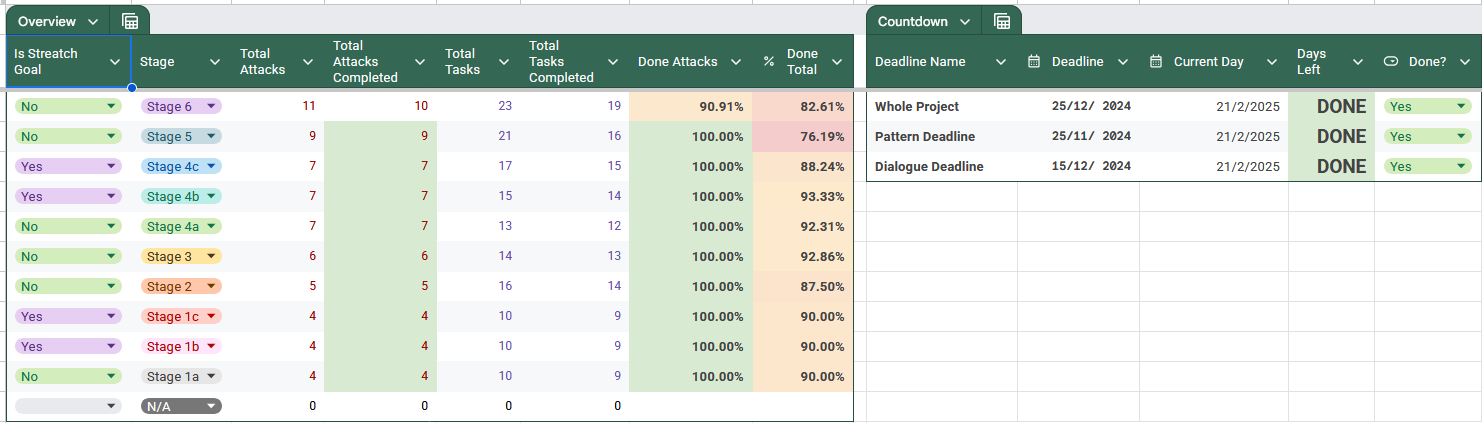

Development Cycle

Because of the scale of this project, I had to do a lot more planning than I usually do for these bullet-hell projects. We were given a time limit of 2 months and I

intended to work on this project daily. As such, organisation and goal-setting was crucial to the completion of this project. I chose to use Google Sheets

for project management as I was most familiar with it and, as I was working alone, had full control over what it looks like.

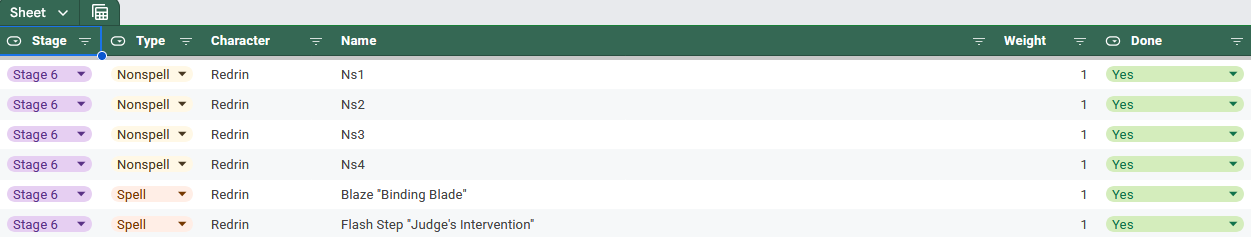

The first tab was dedicated to listing everything that needed to be completed. Each row contained the stage the task tied to, what type of task it was, the

character the task is related to, a name/description of the task, an importance value and its completion status. Tasks were also marked as streatch goals to clearly indicate that

they were to only be finished towards the end.

The next tab was dedicated to tracking progress with numerical values. As the majority of the project’s creative bulk rests in boss attack patterns, progress for each pattern

in each stage was tracked, as well as the total number of tasks related to that stage.

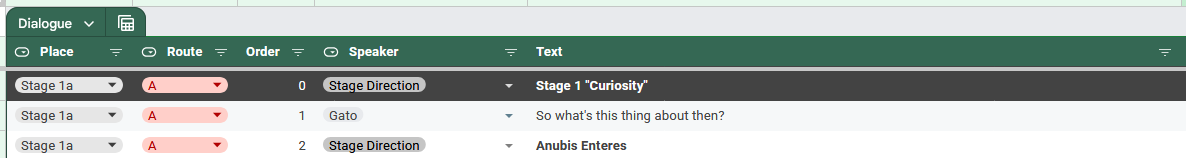

The last tab was entirely dedicated to the game’s dialogue. This allowed for easy tracking of the writing’s progress and gave the co-writers of the project a place to put all

their work.

When it came to reviewing work, I had a small team of play-testers for the gameplay and consultants for the creative aspects. I utilised the Agile methodology when it came

to obtaining feedback and working on improvements.

When it came to time management, I handled everything pretty well. There were very little conflicts in scheduling as I had prioritised everything crucial first. Furthermore,

I understood my own limits as both a programmer and an artist so I understand what I could realistically do within the given time frame.

Brief Engine Context (Yield)

I feel the need to explain this concept as some code design principles are altered to work with this scripting system.

For context, DNH works with functions, tasks and the yield system. Functions work as one would expect in programming languages. You can call them, pass

through parimiters and return data. Tasks are similar to functions, however they are unable to pass data back to the place that called it as these

are intended to run in parallel. This all matters because of the yield funciton. When this is called, the code following it is not executed

until the start of the next frame. When a funciton is called with a yield in it, the code following the call is not ran until all yields within

the function have been passed. On the other hand, when a yield is reached within a task that has been called, the code following the call is

executed.

Brief Engine Context (Script Types)

Without going into too much detail, games made within this engine primarily utilise the following three script types. Package, Stage and Single. These are tags

applied to each script which tell the engine how it should execute a certain piece of code. Package scripts are always running, stages contain gameplay and singles

are used for individual boss attacks. Packages can call for the running of stages and singles and stages can only call for the running of singles. In theory, you only

need stage scripts as much of the funcitonallity can be coded within these, however a lot of existing features of the engined are streamlined with propper use of

all three of these types.

Alongside the script type, the tags also store the name of the attack and any descriptive text which can be read from by external scripts.

Menus

Though something I worked on towards the latter half of the project’s life, I shall go over the menus first. I feel I should go through each aspect of the game in order of when you would

encounter it.

Loading

The menus, and by extention the loading sequence, were simple enough to implement. Implementation took roughly a week in total as I had to design, create assets and code for each screen.

The design of the menu elements, as well as the game UI later, are inspired off of the game Trials of Mana, which

is the gift recipiant’s favourite game. Menus for personal projects like these are more so flourish, as the focus with these games is the gameplay and presentation of the playable bits.

Due to the lightweight nature of all the game’s resources, all the

assets are loaded right at the start of the game. Small note is that the loading sequence plays a small sound at the start to allow people to quickly

adjust their volume before the game starts.

The menu system utilises how functions work when containing yields, ensuring only one menu section is visible at any given time. Each menu segment is its

own function, contianing a transition to and from, as well as the functionality of the menu. As classes do not exist in DNH, the functions were roughly

modelled off of the structure of classes in languages like C++.

As seen in the screenshot above, certain elements of the main menu are blacked out as they require reaching a certain point in the game. Save data in Danmakufu is handled by writing and reading

to a .dat file. You can retrieve certain aspects of save data as all data is tagged with a string. As such, string manipulation is often used to make tracking save data strings simple. Below

is some code borrowed from a fellow DNH developer and reworked for utilising save data to record boss attack score.

LoadCommonDataAreaA2("History", DATA_HISTORY_PATH);

let player = GetPlayerID;

let sp_id = (stage) ~ "|" ~ (pattern) ~ "|" ~ (diff);

let SpellDataAttempt = sp_id ~ "|" ~ player ~ "|Attempt";

let SpellDataGet = sp_id ~ "|" ~ player ~ "|Get";

let SpellValueAttempt = GetAreaCommonData("History", SpellDataAttempt, 0);

let SpellValueGet = GetAreaCommonData("History", SpellDataGet, 0);

SpellValueAttempt++;

SetAreaCommonData("History", SpellDataAttempt, SpellValueAttempt);

SaveCommonDataAreaA2("History", DATA_HISTORY_PATH);

Attack history, player stats, route completion and settings are all saved using this.

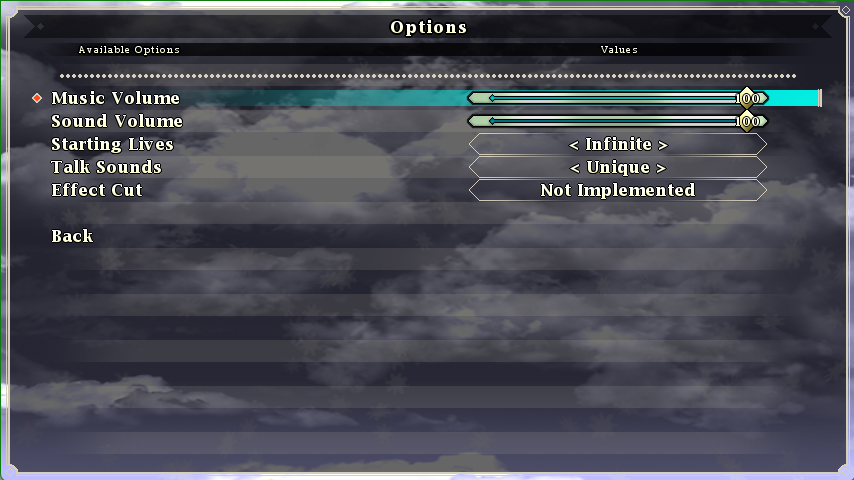

Options

After retrieving the options from the save data, the game upon boot and after the options menu is exited set the according CommonData, which are

essentially global variables.

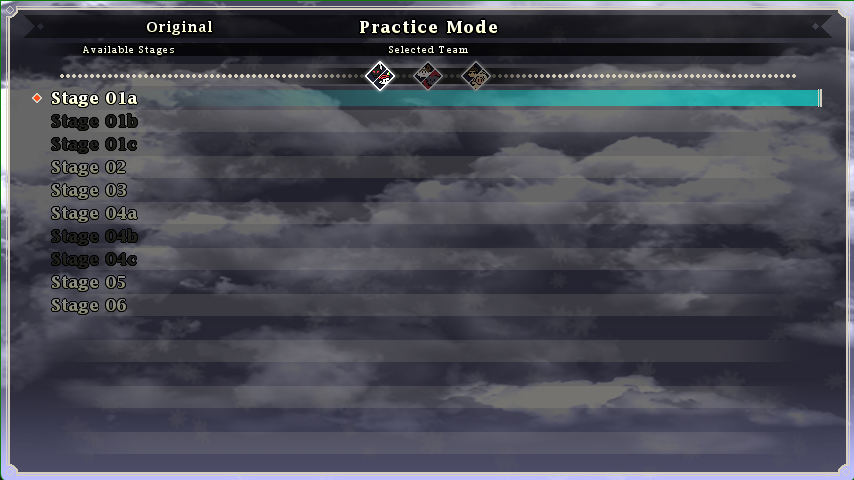

Practice

As shmups require a lot of practice, it was important for me to include a practice menu unlike most of the other projects I have worked on. Here

you can select a stage and a specific pattern to practice as long as you have encountered that attack.

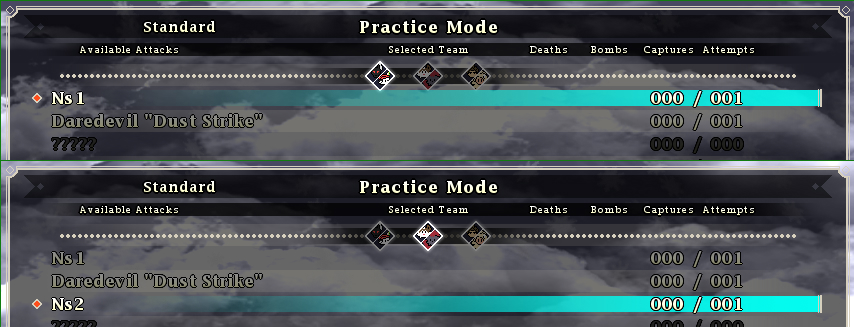

Once on the screen above, you can practice an individual attack as many times as you want. When selected, the package runs the single script ascociated with the attack, as mentioned

previously. The practice menu is designed in a way so that as it automatically presents the available attacks after scanning through each of the single files.

Upon opening, the game immediately makes an array of all available attacks and stages located within the game files and stores them in order of encounter. As such, the following code also

ensures that the attacks are ordered correctly for the practice menu to display.

const AVAILABLE_STAGES = [ PRACTICE_STAGE_01A,

PRACTICE_STAGE_01B,

PRACTICE_STAGE_01C,

PRACTICE_STAGE_02,

PRACTICE_STAGE_03,

PRACTICE_STAGE_04A,

PRACTICE_STAGE_04B,

PRACTICE_STAGE_04C,

PRACTICE_STAGE_05,

PRACTICE_STAGE_06

];

let stage_attack_array = [];

let stage_practice_array = 0;

task InitialisePracticeAttackPaths() {

ascent(i in 0..length(AVAILABLE_STAGES)) {

let stageDir = STAGE_DIR ~ AVAILABLE_STAGES[i] ~ "/";

let allScripts = GetScriptPathList(stageDir, TYPE_SCRIPT_SINGLE);

stage_attack_array ~= [[]];

let nonArray = [];

let spellArray = [];

let foundStage = GetScriptPathList(stageDir, TYPE_SCRIPT_STAGE)[0];

WriteLog(foundStage);

ascent(o in 0..length(allScripts)) {

if(GetFileNameWithoutExtension(allScripts[o])[0] == 'N') {

nonArray ~= [allScripts[o]];

}

if(GetFileNameWithoutExtension(allScripts[o])[0] == 'S') {

spellArray ~= [allScripts[o]];

}

}

let nonCount = 0;

let spellCount = 0;

while(nonCount < length(nonArray) || spellCount < length(spellArray)) {

if(nonCount < length(nonArray)) {

stage_attack_array[i] ~= [nonArray[nonCount]];

}

if(spellCount < length(spellArray)) {

stage_attack_array[i] ~= [spellArray[spellCount]];

}

nonCount++;

spellCount++;

}

stage_attack_array[i] ~= [foundStage];

}

}

Availability of the attack and the history data is also displayed on this menu, and updates accordingly if you switch the playable team.

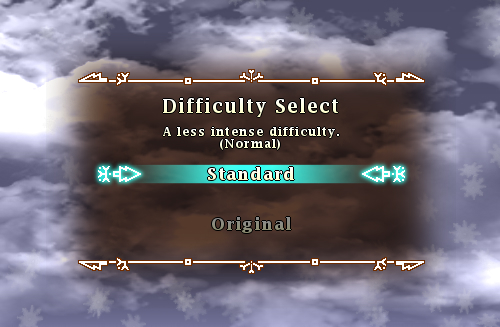

Difficulty and Player Selection

There can only be one active difficulty and playable team at a time. Luckily, only the package script needs to concern itself on which of each is

currently active.

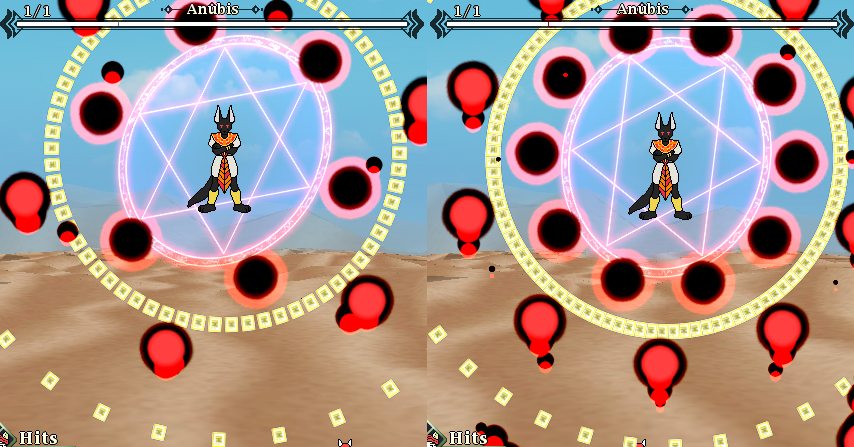

I only intended to implement two difficulties, which has become a standard trope for my work. Balancing will be discussed in a later section.

Implementation of various difficulties within gameplay was very simple. At the start of every attack, the common data determining the

difficulty setting is retrieved and applied to a variable in which all attacks can access. Older works in the community tend to have difficulty variation

be determined by what file is used for an attack. This saves a lot of time and reduces code repetition. Below is an example of how an attack varies depending

on difficulty.

let tot = [6,10][DIFFICULTY];

ascent(i in 0..tot)

{

let ang2 = ang + 360/tot*i*bit;

let x = ObjMove_GetX(objEnemy);

let y = ObjMove_GetY(objEnemy);

let speed = 7;

let obj = BloodShot(x, y, speed, ang2, 1.5, 60, [255,64,64], true);

ObjMove_AddPatternA2(obj, 0, speed, NO_CHANGE, -speed/60, 0, 0);

ObjMove_AddPatternA2(obj, 110, 0, NO_CHANGE, 2/50, 2, 0);

Homing(obj, [1.5,2][DIFFICULTY], 110, 50);

}

Left (Standard), Right (Original)